Osteopathy and its impact on the welfare of zoo animals

Tony Nevin is a trained osteopath living in the UK. He operates clinics for people, small animals and horses, as well as offering consultancy work with wildlife and exotics. He has worked at many zoos and safari parks in the UK as well as several abroad. He has a regular radio show The Missing Link on Corinium Radio, is part of the editorial team for Animal Therapy Magazine and was the main author and editor for Animal Osteopathy – a comprehensive guide to the osteopathic treatment of animals and birds. Tony runs regular wildlife and elephant workshops, sharing his knowledge to help improve the husbandry and general health of these amazing creatures and in our latest blog he discusses osteopathy for animals and how it impacts their welfare.

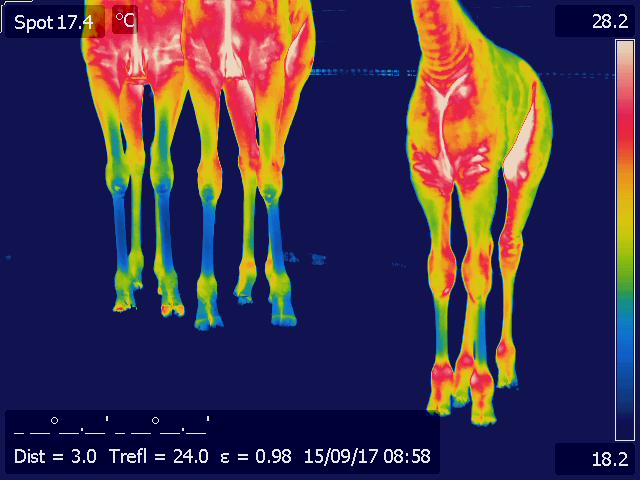

There are many views on the best ways to assess welfare within zoos. As an osteopath, with more than three decades of clinical and research experience, I find it fascinating that my branch of medicine is mostly overlooked when it comes to this subject. Osteopathy is well placed to assess body condition, animal alertness and body language, as well as noting biomechanical issues. Coupled with high definition infrared thermal imaging, it can be an incredible addition to assist monitoring methods when combined with keeper experience and feedback.

Thermal image of elephant foot

Thermal imaging often gets bad press because it isn’t able to give an actual diagnosis of a problem. What it can do, when performed properly, is flag up areas of the body that are not functioning as well as they should. By registering radiated heat given off by an individual’s subcutaneous blood flow, it is possible to roughly map out disturbances to particular regions of the body via the known nerve supply to these blood vessels. The blood flow directly under the skin is supplied by the sympathetic part of the autonomic nervous system, which is a major component of an individual’s central nervous system (CNS). By measuring these surface temperatures, we can gain a window into the CNS and without causing stress through a more invasive technique (e.g. blood testing).

Sadly all too often, I only get called in to treat an animal as a last resort. Health and safety is often quoted as a block for calling in the osteopath, however there are many ways of assessing that don’t require hands on work. Having the knowledge of movement, anatomy, and physiology can be immensely useful in redesigning enclosures, enrichment, and active exercise routines. Using carefully placed additions to an enclosure can subtly transform it into essentially a gymnasium for the physical side of health, as well as the mental component.

Whenever I have been asked to contribute, it has been for a particular patient, and as we know, different animals have their own character. What might have worked for one at a facility might not work with another. This is where the inter-professional working relationship really shows itself. No one knows their animals better than the individual keepers that look after them daily. Finding out what makes animals tick is crucial before starting a treatment and/or rehabilitation plan.

Palpating a patient

Where I have had my best results has been where myself and the animal keepers have gelled and worked together. It’s important for me to understand what is realistically possible and not ask for things that will make everyone’s lives that much harder. Sowing the seed is often all that is needed. Once the keepers know what we need to achieve, they will usually see a better way than me to get the results.

Osteopathy itself is one of the manually applied forms of medicine. Within the United Kingdom it is classified as a primary healthcare profession in the human sector. Within veterinary medicine it comes under the para-professions. That is, those allied to veterinary medicine but requiring a vet to refer or oversee a patient’s treatment program. In other territories the areas are greyer, and as often as not there isn’t any legislature to cover any of it.

There is an urban myth about osteopathy, concerning what we treat. If I had a pound, dollar, or euro for every time someone has said “you only treat bones” I’d be nearly as wealthy as Bill Gates. What we actually treat are disturbances to the musculoskeletal system (MSK), soma or body framework. By MSK I am talking about the skin, fascia, muscles, tendon, ligaments, joint capsules, connective tissues, and the skeleton.

What we aim to do is to restore normal function throughout the entire body. What we don’t do is treat a hip, or a shoulder. Also we are more interested in the quality and ease of overall movement than looking for pure symmetry. Few things in nature are completely symmetrical. We all develop as we grow, and therefore the dominance of each half of our brain, as well as our daily functions and environmental issues, dictate how the adult version of us comes about. There is a wonderful law in osteopathy that states function governs structure, and structure governs function. How and what we use our bodies for, dictates how they grow and wear, and the structure of our bodies will also dictate how we can function. When an injury occurs, it has a direct effect on the MSK. If we are born with a physical or CNS based problem it will affect the MSK.

That is because when we injure or damage a joint, or aspect of a joint’s function, we trigger an immediate response within the CNS that starts a ball rolling to create an inflammatory response, reduce movement through the affected area, and set up compensatory patterns throughout the rest of the body in order to take strain off the affected part. Thus within an hour or two, it is no longer a hip or shoulder problem, but rather a holistic one affecting the whole of the individual to some degree or other.

Therefore by the time I get to see a patient it has a very well established compensatory pattern that I will need to assess and then try to unravel. This is where thermal imaging comes in handy. For a condition to fully resolve, the CNS has to reset everything back to its normal operating settings, in much the same way a computer can be reset to the factory settings.

If a problem is congenital or acquired (such as a dietary deficiency as an infant) then I need to be able to work within a team so that there are experts on diet, as well as keepers who can ensure daily exercise programs that dovetail in with any physical work I may also provide. How treatment is applied will vary from patient to patient. Some can remain fully conscious and standing, whilst others will require full anaesthesia..

Another myth within the manual therapy professions is that anaesthesia, or even just sedation, prevents any feedback to the practitioner when palpating (feeling the quality of the structures under the skin). This is also another area where we, as osteopaths, have much to offer. We are trained to feel what is going on without triggering a defensive muscle spasm or contraction over the contact point. It also makes finding out what is going on that much safer, as some animals lash out when hurt or startled. The reality, after spending my career with patients conscious, sedated, or anaesthetised is that the body gives just as much feedback, without any of the avoidance tactics that an animal might use to avoid an uncomfortable stimulus. By uncomfortable I’m talking about changes in tissue reaction stimuli rather than the practitioner trying to elicit a pain response.

Assessing an elephant in a protected contact setting

Once a patient has been palpated all over, I then have a good idea as to how best to treat it. Each patient will have a preference and subtle tells will be elicited during the palpation phase. Some, such as rhino love lots of deep tissue massage, where they will lean most of their weight on you so that they can release entire muscle and fascial trains throughout their body. Others, like elephants usually prefer sustained positional release work where they lean a particular body part onto me and then release localised structures. This can be performed with the patient standing, and will involve me moving all around with multiple contact points.

With anaesthetised patients such as big cats and great apes, time is the most crucial aspect, as I want to minimise any risks caused by a lengthy procedure. This area is probably the most challenging, as anaesthesia of many wild and exotic species is not a precise science and we’ve had the occasional patient wake up when I’ve applied a particular technique. Most commonly, this is where I’ve released tension at the very top of the neck where it joins the skull.

Most patients I treat have established compensatory patterns, and as such require a series of osteopathic treatments. Some, such as elderly patients, require ongoing maintenance treatments. Experience has taught me how long we can space these out before we see degradation in the patient’s health and well-being.

The future is wide open for further integration of osteopathy into improving zoo animal welfare. Rather than waiting for a problem to occur, it is getting much more plausible to do simple, non-invasive assessments of animals to ensure that they are not showing any signs of impending health and welfare issues. Keepers can do the majority of this, with an animal osteopath available to do more in-depth assessments as well as assessing movement patterns of particular individuals. Therefore osteopathy has a lot to offer zoo animal welfare, and the zoo profession as a whole.

Images © Zoo Ost Ltd.

The views, opinions and positions expressed by guest bloggers are theirs alone, and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of Wild Welfare or any employee thereof. Wild Welfare is not responsible for the accuracy of any of the information supplied by the guest bloggers. We accept no liability for any errors, omissions or representations. The copyright of this content belongs to the author and any liability with regards to infringement of intellectual property rights remains with them.