Assessing dolphin welfare: making the debate ethical

Dr Isabella Clegg is a marine biologist and welfare scientist, and founder of the organisation Animal Welfare Expertise (AWE). Isabella discovered that while animal welfare science continued to progress, the transfer of knowledge into the various animal industries was lagging behind. She founded AWE to help fill the gap and offer simple, innovative tools to evaluate animal welfare and ensure quality of life for captive and wild animals. In this blog Dr Isabella explores the latest scientific and ethical questions around captive marine mammals.

The evidence base for zoo animal welfare has increased exponentially in recent years, and dolphin welfare is no exception. The first few indicators of dolphin welfare have now been identified, their level of optimism has been tested in captivity, and comprehensive assessments are being developed and applied in situ.

Historic management practices were certainly not optimal for dolphin welfare, and although conditions have improved, these animals are still set slightly apart from the general zoo community, likely due to the continued show-style presentations and animal-visitor interaction programs. Furthermore, NGOs and other campaigns rightly highlight the poor practices occurring in less developed countries, especially where there is continued capture from the wild.

Despite this, recent objective results on dolphin welfare suggest that the story is not so black and white: looking at the peer-reviewed literature, it seems as if there may also be objective signs of positive welfare in dolphins.

These findings suggest we may need to refocus the public debate on the issue of captive dolphins and instead of encouraging speculation on the dolphins’ welfare state – which we are now starting to get objective answers on – it would be more productive to understand what the public’s ethical viewpoint is on the practice.

For most people, if assessments showed that animals were experiencing poor welfare, the practice would not be acceptable. But, hypothetically, if dolphins were confirmed to be experiencing good welfare, would the public support them being in captivity?

Assessing dolphin welfare

Being a dolphin welfare scientist, I’ve had a lot of time to ponder these questions. I studied animal welfare, then marine mammal science, before completing a PhD on measuring dolphin welfare in captivity. But although I loved conducting research, I was most interested in applying measures to the dolphins themselves, and helping to improve welfare on the ground.

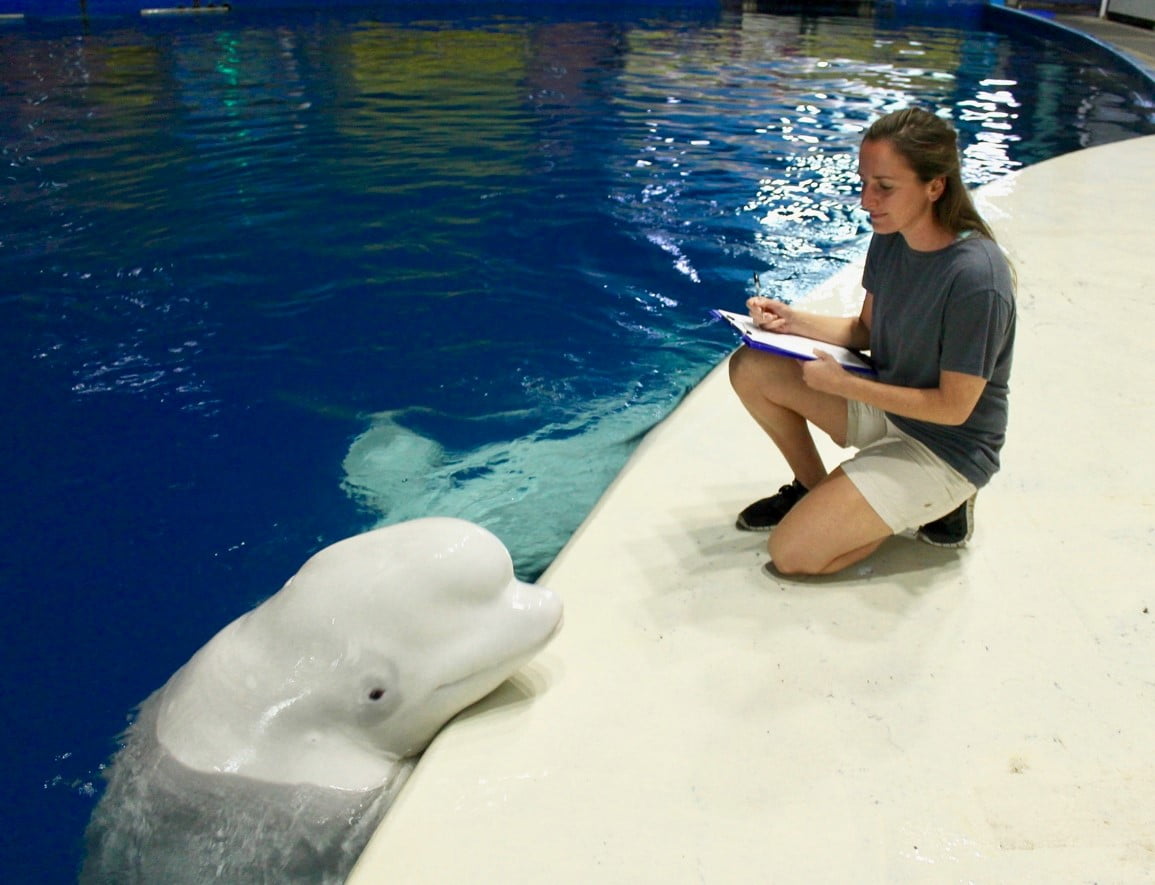

This led me to start the Animal Welfare Expertise consultancy, and I now conduct welfare assessments of dolphins (and other zoo animals) around the world, improving management and helping those caring for captive animals to monitor animals’ emotional states in real-time. Some of this work is leading me to the forefront of where public opinion is acting on cetacean welfare issues: for example, I’m working with the SEA LIFE Trust on their Beluga Whale Sanctuary Project – the movement of two belugas from China to an open water bay facility in Iceland. My role is to assess their welfare in China, and then over several periods of their adaptation to their new environment in Iceland, providing information on whether the move improves their welfare.

Although there is a huge public and media focus on dolphin welfare in captivity, there is actually very little objective information or peer-reviewed science on the issue, although this has changed in the last few years – likely stimulated by increased public interest and progress in farm animal science – and there are now studies on these animals’ emotional lives in captivity.

So, what has this work shown us so far? While there are certainly published studies finding poor welfare in captivity, there are also results emerging showing objective signs of positive welfare. For example, social stress can cause poor welfare and even death for captive dolphins1 and it was found that salivary cortisol and stereotypic swimming patterns were higher in closed, smaller pool systems as opposed to larger sea pen facilities2. On the other hand, dolphins were found to positively anticipate and approach trainers for sustained non-food interactions3 and when cognitive bias testing was applied (where the animals’ degree of optimism is measured, which reflects positive welfare), dolphins that swam synchronously more often were found to be optimistic in captivity4.

And this exactly reflects what I’m seeing on the ground when I assess dolphin welfare, using the animal-based C-Well Assessment (a welfare assessment index for captive bottlenose dolphins).

Some modern facilities provide much daily stimulation for the animals and have good levels of welfare, while others are cutting corners and the animals tend to be in poorer welfare.

Ethical crossroads

In my mind, these findings are much the same in other zoo collections, where modern zoos are working very hard and optimising the welfare of their animals, while other zoos are not achieving this and are dominating the media and public perception. Given the advances in animal welfare science, and the real possibility that we could ensure that zoo animals (including dolphins) can exist in captivity in good welfare, I think it’s time to ask the more important question of why they are there. For many, the crux of the issue will be whether it is acceptable for captive animals (even those in good welfare situations) to be primarily used for entertainment, for conservation or for research and education, or not at all?

Despite the uncertainty over public opinion on the issue, legislation is moving fast in this area. Only a few weeks ago, Canada passed a bill making it illegal to hold a whale, dolphin or porpoise in captivity and the US company SeaWorld has committed to end captive breeding. Exciting developments are being made in the field of dolphin welfare research, showing signs of positive and negative animal welfare for captive species, but the public and legislators don’t currently seem to be engaging with them.

The debate on captive dolphin welfare is no different than for other zoo animals, and the important ethical questions on the purpose of wild animals in captivity deserves more focus.

Further information:

You can listen to more of Dr Isabella’s work on YouTube and connect with her via Twitter, Instagram and Animal Welfare Expertise.

- Waples, K. A., and Gales, N. J. 2002. Evaluating andminimising social stress in the care of captive bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus). Zoo Biol. 21: 5–26.

- Ugaz, C., Valdez, R. A., Romano, M. C., and Galindo, F. 2013. Behavior and salivary cortisol of captive dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) kept in open and closed facilities. J. Vet. Behav. 8: 285–290.

- Clegg, I. L. K., Rödel, H. G., Boivin, X. & Delfour, F. (2018). Looking forward to interacting with familiar humans: dolphins’ anticipatory behaviour indicates their motivation to participate in specific events. Applied Animal Behaviour Science. 22, 85-93

- Clegg, I. L. K., Rödel, H. G. & Delfour, F. (2017). Bottlenose dolphins engaging in more social affiliative behaviour judge ambiguous cues more optimistically. Behavioural Brain Research, 322, 115-122.

Image © Beluga Whale Sanctuary: Dr Isabella carrying out behavioural observations of the beluga whales

The views, opinions and positions expressed by guest bloggers are theirs alone, and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of Wild Welfare or any employee thereof. Wild Welfare is not responsible for the accuracy of any of the information supplied by the guest bloggers. We accept no liability for any errors, omissions or representations. The copyright of this content belongs to the author and any liability with regards to infringement of intellectual property rights remains with them.